When William Golding’s Lord of the Flies was published in 1954, it met with almost universal critical acclaim. By the 1960s, the novel was also a phenomenal commercial success, particularly in America, where the book had captured the imaginations of undergraduates and become a set text on many literature programs. From its initial publication, a number of studios, both British and American, were interested in the film rights although the violence depicted in the novel meant that any film adaptation would only receive an ‘X’ certificate which studios were unhappy with. Eventually, the theatre director Peter Brook secured a small amount of funding to make the film, which was released in 1963.

Brook’s film is entirely shot in black and white and filmed on an island off the coast of Puerto Rico. Budgetary constraints meant that he couldn’t bring boys from England so he cast the film ‘from English boys who happened to be closer to hand’ (Carey, William Golding, 274). The majority of the boys were not ‘actors’ as such, and the script was largely improvised. In addition to the inexperience of the child actors, many of the crew members had never been involved in film production before.

All these elements contribute to the power of the film and its documentary-like feel. The background to the crash on the island is dealt with in a series of stills featuring quintessential shots of English schoolboys followed by images of evacuation, planes and warheads. Much as Golding’s original text did not delve into the detail of this war, the film also offers little explanation for the war. Brook clearly identifies that the action on the island is at the heart of this story rather than the background.

The film is generally faithful to Golding’s original text; many of the lines spoken come directly from the book. Brook ensures that the audience can distinguish between the boys by having the main characters introduce themselves at the beginning of the film. The scene where Jack and his singing choir walk across the beach in harmony is prophetic of events to come and when Roger introduces himself, those viewers ‘in the know’ can sense something different about him. The bullying of Piggy begins in this all-important scene, as does the struggle for leadership and power between Ralph and Jack. Simon faints at the meeting and Jack tells the others that this is a frequent occurrence, thus setting Simon apart from the others.

One notable aspect of the book missing from the film is Simon’s conversation with the pig’s head. Of course, this would be difficult to film without looking ludicrous, particularly without the benefit of special effects or CGI. However, Simon stares intently at the pig’s head and the camera lingers on the pig’s mouth, perhaps giving the impression of conversation. After his encounter with the pig’s head, Simon discovers the truth behind the beast and rushes back to the beach to tell the others. This scene, when Simon returns to the boys who are all dancing around the fire chanting ‘kill the beast’ and is beaten to death, is emotionally intense and beautifully shot. It is dominated by the screams of boys, the heavy impact of sticks and the crashing of either thunder or waves (perhaps both). As we see Simon’s dead body in the sea, the camera pans to lights reflected in the ocean backed with haunting choral music.

The final chase sequence at the end is exhilarating. Jack’s group chase Ralph through burning foliage, getting progressively louder as they begin to catch up to him. This cacophony of sound is abruptly quieted when Ralph runs into a man on the beach. The arriving sailors survey the boys in bewilderment as Ralph cries into the camera. The final scene does disappoint me in one respect – the naval officer does not speak when he finds the boys. In Golding’s novel, the officer at first thinks that the boys have been playing until Ralph tells him that two boys have been killed. The realisation of the savagery and war on the island leads to the officer’s ironic statement, ‘I should have thought that a pack of British boys … would have been able to put up a better show than that’ (222). It is surprising that Brook chose to omit this particularly as Jack says early on in the film, ‘After all, we’re not savages. We’re English’.

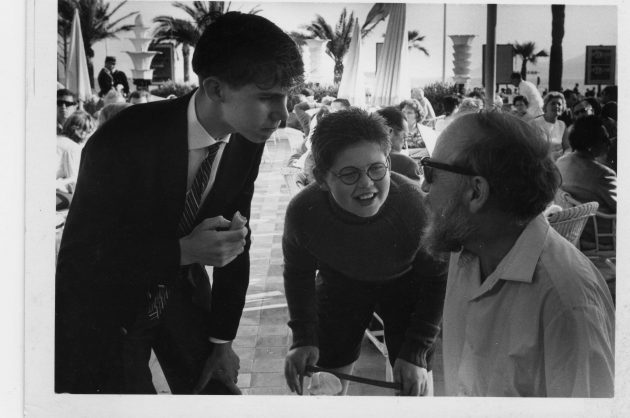

Despite this small disappointment, the film is a wonderful adaptation of Golding’s novel and one that Golding himself approved of. Golding’s daughter Judy states that she felt ‘her father was very impressed by Brook’s film’ (Carey, 275). Read more about Brook’s thoughts on the film.

1990 film

Unfortunately, the same praise cannot be applied to the second adaptation of Lord of the Flies. Released in 1990 and directed by Harry Hook, the British public school boys have been replaced by American military cadets. Many critics have complained about the change of nationality but I think the biggest problem lies in making the boys military cadets. Cadets would have been taught basic survival skills, would be used to following orders and therefore would find surviving on the island far easier than Golding’s schoolboys. The chain of command on the island already seems established before their initial meeting with the younger children calling Ralph ‘sir’. When Ralph declares himself to be chief, Jack concedes with almost no protest, making his later demand for power rather inexplicable.

The boys in Golding’s novel appear to be strangers when they crash on the island (with the exception of Jack’s choir) but in Hook’s film, they appear to know each other. This makes it difficult for the viewer to differentiate between the majority of the boys – they aren’t introduced and due to a lack of distinguishing features, appear almost homogenous. Piggy endures a similar level of bullying in the film as he does in the book but Ralph explains to him that this is because he is the ‘new boy’. Piggy is bullied in the novel because of the way he looks and his priggish behaviour, not because of any prior conflict or relationship.

The major factor in the novel that propels the boys into savagery is the fact that there aren’t adults. As Ralph says, ‘There aren’t any grown-ups. We shall have to look after ourselves’ (36). However in the film, the pilot is rescued from the sea and lies in a tent, seriously injured but alive. These boys are not by themselves and the pilot’s presence is entirely unnecessary. Some of the children discuss what to do about the man, implying an act of violence, so he escapes from the boys’ camp and hides in a cave. When he is eventually spotted, he becomes the ‘beast’. Before his escape, Simon is charged with looking after the pilot and in an attempt to show that Simon has some kind of special ability, he has foreboding dreams of death, bordering on the prophetic. However, Hook entirely fails with the episode with the pig’s head; it is inappropriately described by Jack as a ‘present’ [which just sounds plain wrong] for the ‘monster’ and Simon’s encounter with the head is quickly dismissed.

The major flaw of the film, aside from the boys being military cadets is the character of Jack. As discussed above, he seems happy to let Ralph be leader but when more details are revealed about him, it transpires he was forced to be in the military cadets because of a previous misdemeanour. Thus Jack is a ‘criminal’ before the crash on the island and therefore already has the capacity to commit savage acts. This entirely misses the point of Golding’s novel; the book has such an impact because these are ordinary boys who are driven to behave in such a way because of a lack of authority and consequence for their actions. Although Golding’s Jack is clearly arrogant and haughty, he is the head boy of his school, which suggests that he is well behaved and a figure of respect.

All in all, neither of the film adaptations are perfect but Brook’s 1963 film comes closest to realising Golding’s vision. It is a beautifully shot and enthralling dystopian nightmare. Hook’s 1990 film is, to be frank, best avoided.