We are offering support for students and teachers. Please click here.

Lord of the Flies was adapted into film twice in William Golding’s lifetime – first by Peter Brook in 1963, and second, by Harry Hook in 1990. Although Golding had no direct involvement with either of these adaptations, the Brook film definitely made more impact on him. Using Golding’s unpublished journals, interviews and biographies, we can get a sense of what he thought about his novel on film.

Lord of the Flies was first published in 1954, and film rights were discussed shortly after, although the violence in the book meant that a film would be difficult due to censorship rules at the time. Peter Brook later brought the book to Oscar-winning producer Sam Spiegel’s attention and John Carey writes about Spiegel and Golding’s meeting in his biography.

Spiegel: Mr Golding, I think it would be a much better story if there were girls as well as boys…

Golding: I wanted the film to be an allegory on the human race […] if you bring in boys and girls you’re forced to bring in secondary side issues, sexual attractions, conflicts, problems of puberty… (216)

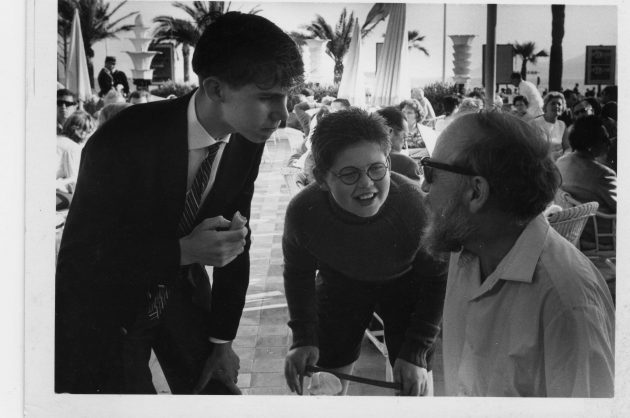

Spiegel was disappointed that Golding could not be persuaded to his way of thinking and abandoned the project. But Brook’s interest continued, and his own film was released in 1963, when it was nominated for the Palme d’Or. Golding and his daughter Judy attended the Cannes Film Festival and Judy recalls in her memoir, The Children of Lovers:

‘[Peter Brook’s] version of Lord of the Flies astonished and gratified my father. Its fidelity to the novel was awe-inspiring. The young actors were convincing, the music sharply moving, the photography startling with the black and white brilliantly showing the heat and the blood’ (274).

In an unpublished journal entry in 1974, Golding was inspired to write about his relationship with Peter Brook after reading an article about him in The Guardian. He wrote:

‘It set me thinking just a little of the past. I met Peter first, when led, as it were, before Sam Spiegel. I think we both felt allied against this colossus of the screen […] I think [Brook] is a genius; and what is more, an evolving one so there is no knowing what he may do and achieve. His high spot for me – though I haven’t followed all he’s done – was his fabulous Dream.’

Golding also wrote about the complicated relationship between the author and adapter in the same entry, a subject he would discuss in interviews. Listen to this clip of Golding responding to a question about his thoughts on Brook’s film version.

In summary, Golding says,‘I had a film of Lord of the Flies unwinding in my head when I wrote it. To put against that technicolour epic in my head – here is somebody else’s idea which much necessity must be a boiled down version of the novel and I can’t get the two into focus – the one with the other. I cannot have a just appraisal of the film. Peter’s intentions were absolutely honest and I think he approached the whole thing with great integrity.’

The evidence shows that Golding was not pleased with the direction of Harry Hook’s 1990 film. In November 1989, he wrote to Charles Monteith, his editor at Faber & Faber: ‘I haven’t seen it, have dissociated myself from it and propose to stay that way!’ (Carey, 500). Golding writes very little about this adaptation in his journals, although he does mention that requests for autographs and fan letters increase after its release. He writes, grumpily but amusingly, ‘What is vexing or sort of vexing is that I am now beginning to get letters which are the result of the second film of the book. I won’t read them!’

Carey does note, however, that Golding’s dissatisfaction about Hook’s film led him to finally agree to a theatrical dramatisation of his novel, completed by Nigel Williams in 1990. This fine adaptation is still performed around the world and Golding attended the premiere, in 1990, with ‘tears in his eyes’ (500).

All extracts from William Golding’s journals are owned by William Golding Ltd and no part of them can be reproduced without permission.